Learning the future

Second installment of updates about experiments in data rights education through workshops, performances, and zines!

All summer long I’ve been writing and studying, exploring data justice, and finding new ideas to use in grassroots experiments with my community in Houston. As a lifelong learner, I love finding patterns and lessons in the world and am inspired by visionary people who are looking over the edge at how we might reclaim control over data and technology for our collective future.

In this Dispatch, I’ll share a little bit of what I’ve been learning from artists, organizers, friends, and collaborators working against surveillance and for community control over data. Carving new neural pathways, letting emerging lessons shape our work — that’s how we’ll find our way to a just data future.

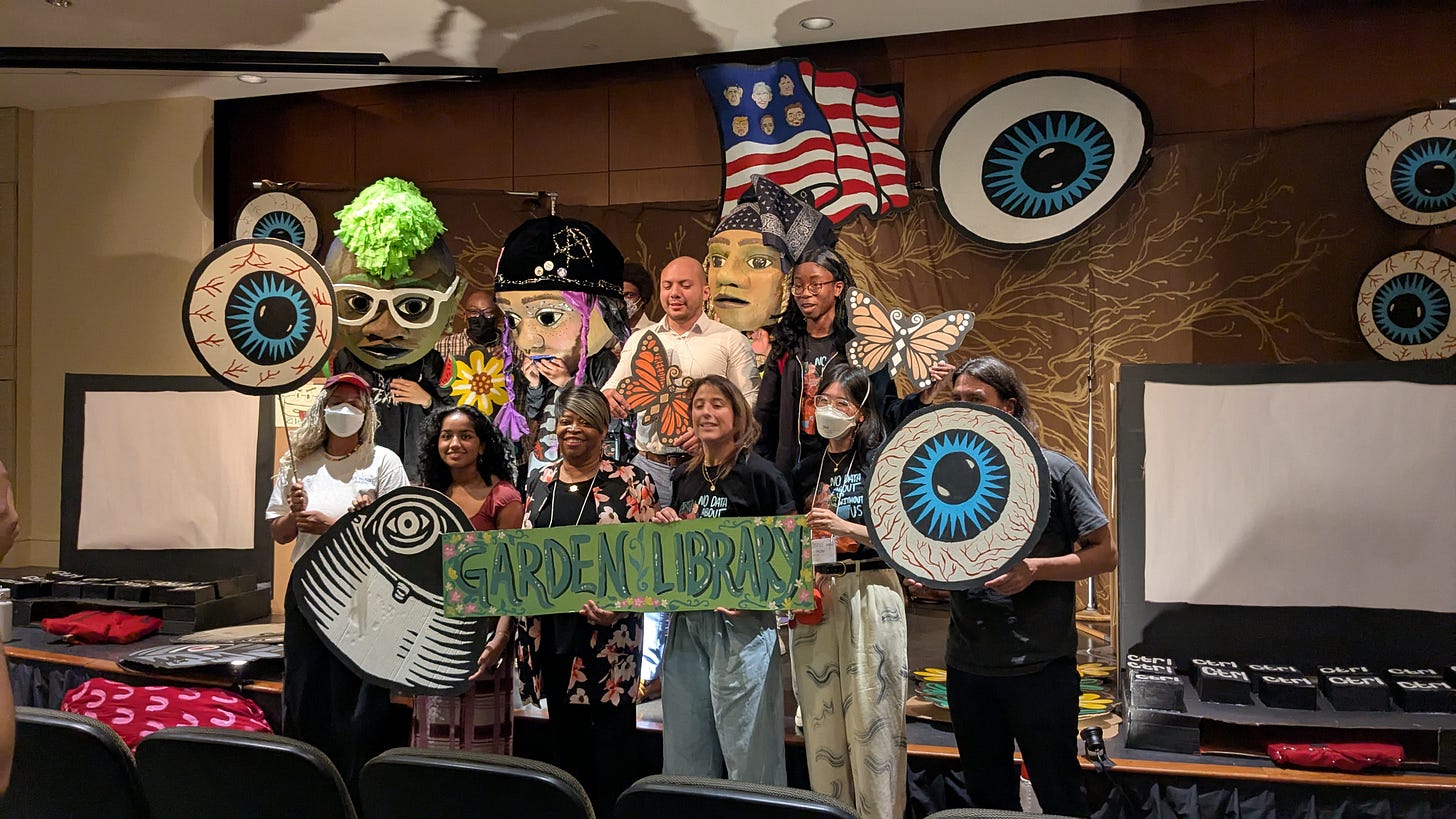

🎓 Giant puppets tell the story of students under surveillance… At the Twin Cities Innovation Alliance’s Data for Public Good conference this past July, students, artists, academics, and organizers came together to discuss topics like critical data science, issues of criminalization and surveillance in AI, and education technologies in media.

All year, the NOTICE Coalition has led No Data About Us Without Us Fellows through a series of educational workshops and research projects to understand and name the challenges they face related to surveillance in their schools. Artist KillJoy and their mycelium network Kitchen Table Puppets & Press worked with Fellows to build puppets and craft a performance that would shed light on types of surveillance that students face, from vape detection technologies to attendance tracking systems.

The performance followed three puppet-students who face different kinds of profiling and policing because of surveillance used in their schools. One student is sent to the “Learning Center,” a high-surveillance alternative school, after searching for banned information on school computers — a growing problem as the State of Texas enacts book bans and stifles freedom of speech in schools. Other characters spoke to the challenges that students with juvenile correctional backgrounds or undocumented family members face when they’re targeted for disciplinary action by any number of surveillance technologies that schools have at their disposal.

Closing with a passionate spoken word poem presented by teacher and organizer Jeremy Eugene, “Digital Dystopia” helped people feel the injustice that students and teachers experience when schools hold their students down under policies of unlimited surveillance and punitive data systems.

Experiments: Grassroots data collectives

Are you someone who is currently experimenting or has experimented in the past with community owned data infrastructure to support movement organizing or advocacy?

One benefit of being known as the town “data person” in organizing spaces is that I get to talk with people in the very early stages of their questions or ideas about how to use data in their work. As I’ve long suspected, most people don’t need dashboards or visualizations to solve all their problems, at least not until the very end of their projects when it’s time to communicate what they’ve found.

Needs that do arise when I’m talking to people include some that data folks might recognize from across contexts: The need to better understand our own behavior and long-term patterns or trends in the issues that we’re tracking in our communities; the need to have difficult conversations about the guardrails around how we collect and store community data when we plan to use it to advocate in spaces of power.

One day some of these projects might be developed enough to share about in public, but for now I’m interested in hearing from anyone who has built data infrastructure specifically with the intent of community ownership, especially building self-hosted databases; or anyone who has created community data licenses to protect data in partnerships with research and academic institutions. If this is you, email me at katya@peoplesdataproject.org!

💡 Crafting a new lexicon to meet the moment…

In my last Dispatch, I explained how the term “unjust data narratives” captures a deeply felt paradox that people feel when they look at data-driven stories about them that fail to reflect their lived realities.

Further building out the lexicon around data justice, today I’m going to share a few of the concepts guiding my decision to use the term “data extraction” to explain how institutions and industry collude to generate power or profit from collection, analysis, and use of our data.

“Extraction” as a concept → The phrase “data is the new oil” was originally introduced by proponents of industry in the beginning of the 21st century as an overall positive and exciting concept driving the future of big data and algorithms. Despite the phrase being somewhat worn out and receiving relatively minor critiques from data policy world, it captured an actual sentiment in the private sector that their goal would be to extract as much of this valuable asset from people and communities as humanly possible. As I talk to people in my own community about concepts of data justice, using the word “extraction” is what shifts their mindset from innocent data “collection” toward the reality of actual exploitation of community knowledge.

“Data Entrapment” as a parallel term → Another angle on data extraction, data entrapment is a term proposed by Marika Pfefferkorn in her article Data Justice and the Risks of Data Sharing to expose how institutions capture and manipulate data for the purposes of enacting their own agendas which may in turn be harmful to youth and communities. Thinking about extraction and entrapment as adjacent also allows us to compare different power dynamics that are at play when data is held by industry or institutions.

Ontologically treating data as a natural resource → I learned through my previous research on data rights and Indigenous Data Sovereignty that Indigenous forms of knowledge arise from land-based, embodied practices sometimes emerging from data gathered by humans to understand their natural environments. Considering data this way, it makes sense to connect the extraction of data to the extraction of lands, much like how colonial systems seek to control Indigenous lands and as a result also require control over or extraction of Indigenous cultural practices and knowledge. Understanding data as something connected in essence to natural systems helps us realize that its extraction without embodiment in context fundamentally disconnects data from its true purpose.

Wait — I have some questions!

Before I go any further, I would like some input from you, my readers! I want to prioritize making and sharing things that you care about the most. As I travel through places and conversations picking up threads to weave together for this newsletter, I’d like to be guided by the things that really energize you.

Thank you for participating in this community poll! Your insights will help me grow Civic Source to become a trustworthy, energizing part of your work and practice.

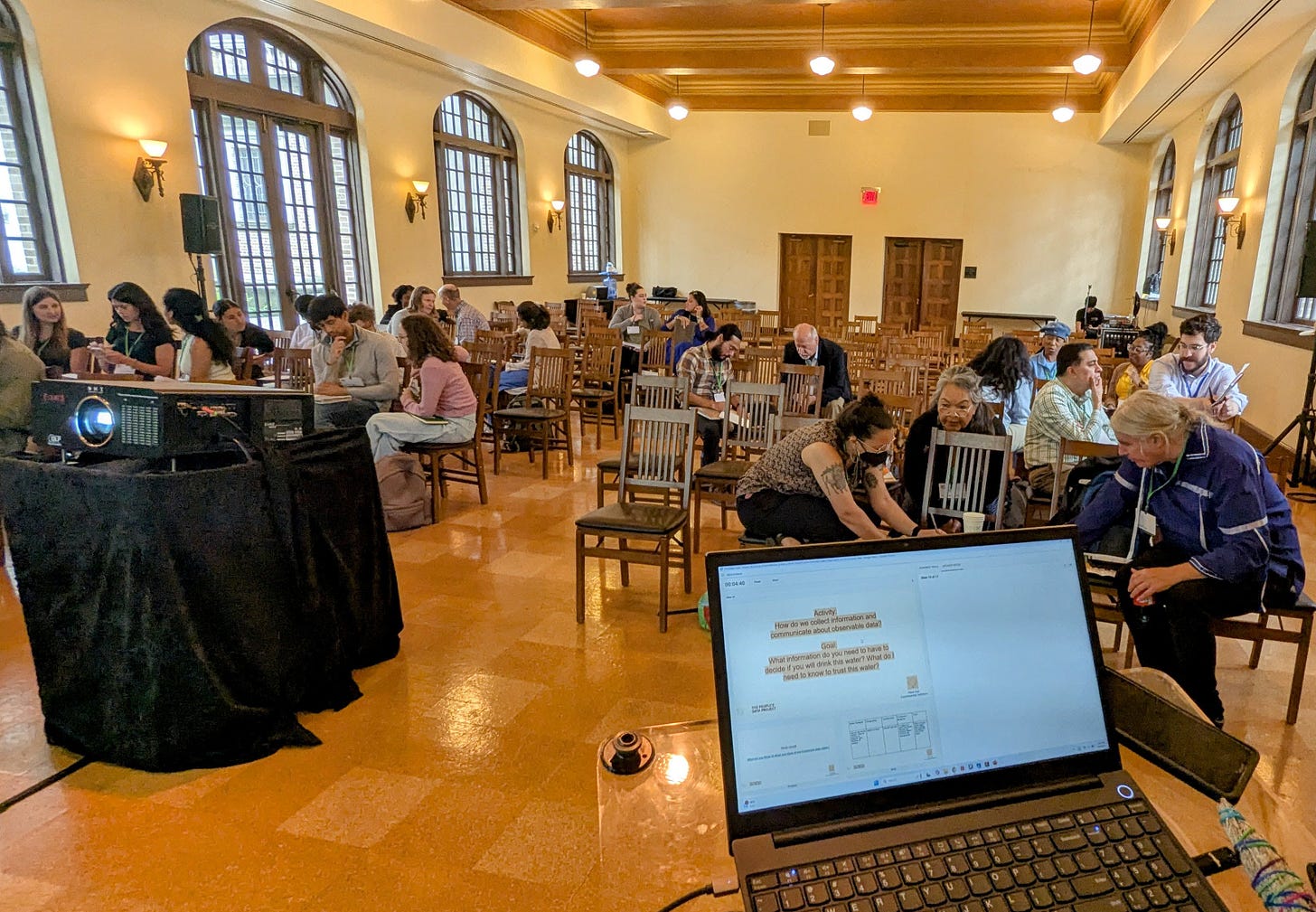

🛠️ Seeding workshops & a data rights curriculum… Now on the People’s Data Project website is a write-up of this summer’s data justice workshops and events! From the Twin Cities to Taipei, I’ve been fortunate to collaborate with folks who are applying data justice in new and interesting ways, bringing tools and resources to folks around the world. We talked to environmental justice advocates, researchers, human rights activists, students, teachers, and tech workers, all of whom are seeing issues of data injustice appear throughout their work.

Many thanks to Emelia Williams at the Open Environmental Data Project and Mashal Awais at Third Pole Solutions who helped co-create these workshops with me. Stay current with the People’s Data Project by subscribing for updates through our wesbite.

Where I’ll be next…

Voqal Fellowship Alumni Reunion, Phoenix, AZ, October 8-12

Know anyone doing data work in Bogotá or Medellín? I’ll be on a mini-research trip and visiting family in December and would love to connect with new allies!